RETURN to Periodic Table

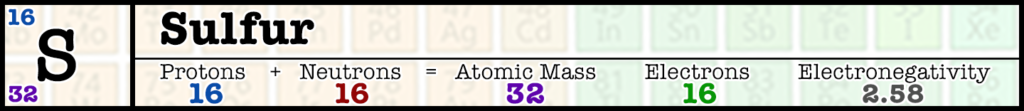

Sulfur is the 16th element on the periodic table. It has 16 protons and 16 neutrons in the nucleus, giving it a mass of 32 amu, and it has 16 electrons enveloping the nucleus.

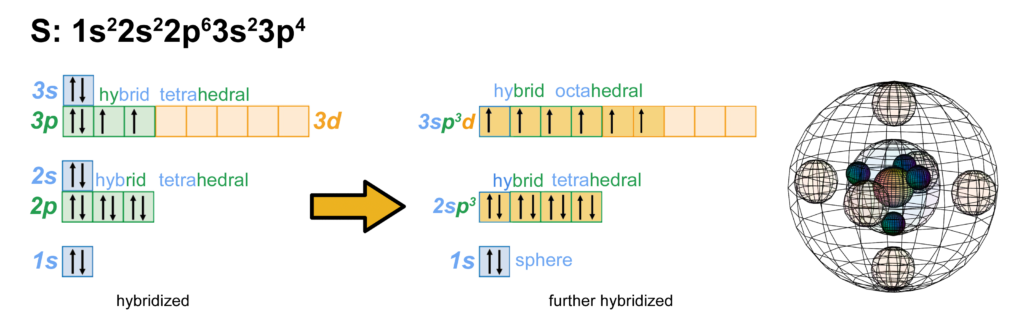

Electron Shell

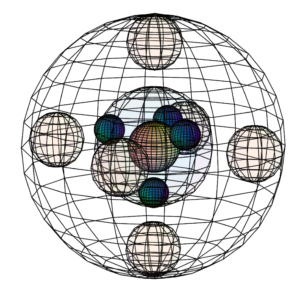

Sulfur has the same electron configuration as oxygen, though as a larger atom and one with a d-orbital into which it can hybridize, sulfur has different properties and can make different molecular geometries than oxygen. (The wireframe indicates the boundary of the n=3 shell.)

CLICK HERE to interact with this object.

CLICK HERE to interact with this object.NOTE: The small spheres in the image above simply indicate the directions of maximum electron density. The 3rd shell orbitals themselves will be more like spherical tetrahedra. The entire shell will be filled with electron density. It will be highest at the center of the face of each orbital (as in the traditional sp3 lobe shapes) and will decrease toward the nodal regions between orbitals, where electron density will be lowest (though not zero). Like argon, sulfur features two nested spherical tetrahedra, the inner 2nd shell comprising 4 di-electrons, the outer 3rd shell comprising 2 di-electrons and 2 single electrons. In this case the two orbitals containing the di-electrons (dark pink) will occupy slightly more volume than the two containing an unpaired electron.

Bonding & ion formation

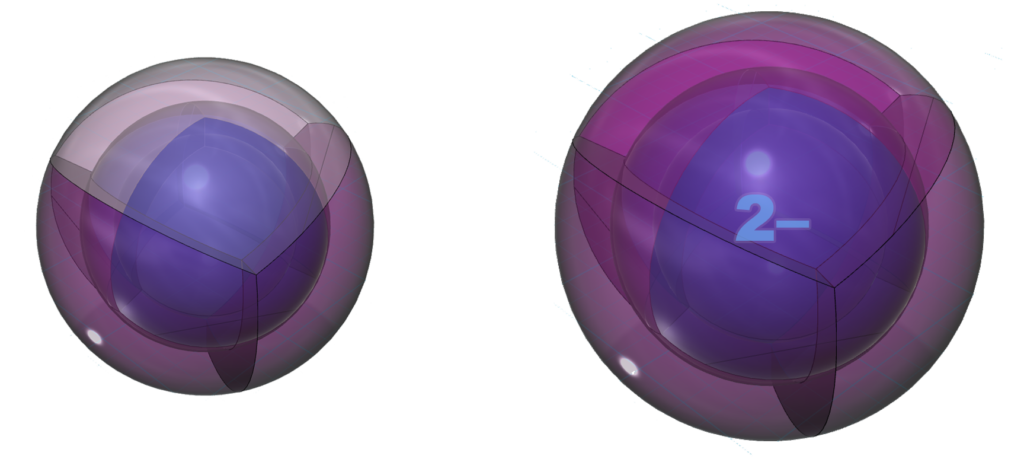

As the structure below indicates, it is common for sulfur to make two bonds. In its natural crystalline form, sulfur forms S8 rings where each sulfur atoms is bonded to two adjacent sulfur atoms. Like oxygen (though not quite as strongly), sulfur is keen to gain two electrons in an ionic interaction in order to reach the stability of the 3s23p6 noble gas configuration of argon, which is a multi-di-electron state with three concentric full shells. That is why sulfur forms a 2– ionic state. The negative ion is much larger than its neutral version because electrons now outnumber protons by two. This results in a lower effective nuclear charge — a lower average attraction by the nucleus on each electron, which expands the size of the electron shell as it is attracted inward with less force.

But if sulfur is approached by highly electronegative atoms like oxygen or fluorine, they can induce sulfur’s paired valence electrons to uncouple, yielding 6 unpaired electrons available for bonding. This is only possible because the 3rd shell contains a d-orbital. While sulfur does not usually have electrons in its 3d-orbital, the 3rd shell has enough volume to accommodate those orbitals. This allows sulfur to hybridize into those empty d-orbitals and to make up to 6 covalent bonds, as we see in the octahedral SF6 molecule.

CLICK HERE to interact with this object

CLICK HERE to interact with this objectUses

Sulfur is an abundant element and has a great many uses in nature, biology and chemical technology.

Sulfur is a relatively common atom in protein structures, and it is therefore present throughout the nutrient cycle, as well as being a waste product from the purification of natural gas and oil, which derive from organic materials.

One common form of sulfur in nature is in sulfide molecules, for example hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas, which is experienced as that notorious ‘rotten egg’ smell. Another is the sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas.

One of the most stable forms of sulfur in nature is the sulfate ion (SO42–). When two electrons are made available by a nearby metal atom, 1 sulfur atom and 4 oxygen atoms can form a symmetrical, tetrahedral arrangement where every atom has a full and symmetrical outer electron shell. Sulfates are a key nutrient in nature.

RETURN to the Periodic Table