RETURN to Periodic Table

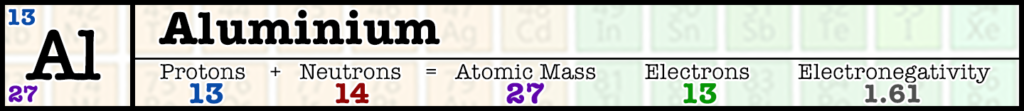

Aluminium (or Aluminum) is the 13th element on the periodic table. It has 13 protons and 14 neutrons in the nucleus, giving it a mass of 27 amu, and it has 13 electrons enveloping the nucleus.

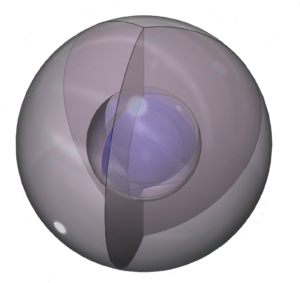

Electron Shell

Aluminium has interesting chemistry and bears similarities to several different elements. It lies in Group III beneath boron, and with a 3p1 electron configuration, it is similar to boron’s 2p1 configuration. This implies that it will form a triangular (sp2 trigonal planar) geometry. It also has similarities to beryllium and can form bonds of a covalent nature. However, since aluminium is larger than boron, its valence electrons fill a larger volume and are therefore less coherent as a single quantum system. This makes aluminium more metallic in nature than the semi-metallic boron above it. (The wireframe indicates the boundary of the n=3 shell.)

CLICK HERE to interact with this object.

CLICK HERE to interact with this object.NOTE: The small spheres in the image above simply indicate the directions of maximum electron density. The 3rd shell orbitals themselves will be more like three longitudinal sections. The entire shell will be filled with electron density. It will be highest at the center of the face of each orbital (as in the traditional sp3 lobe shapes) and will decrease toward the nodal regions between orbitals, where electron density will be lowest (though not zero).

Each of these three hybrid orbitals contains one electron. Like boron’s configuration, this arrangement is symmetrical in the equatorial plane but does not have equivalent symmetry in all directions.

Bonding & ion formation

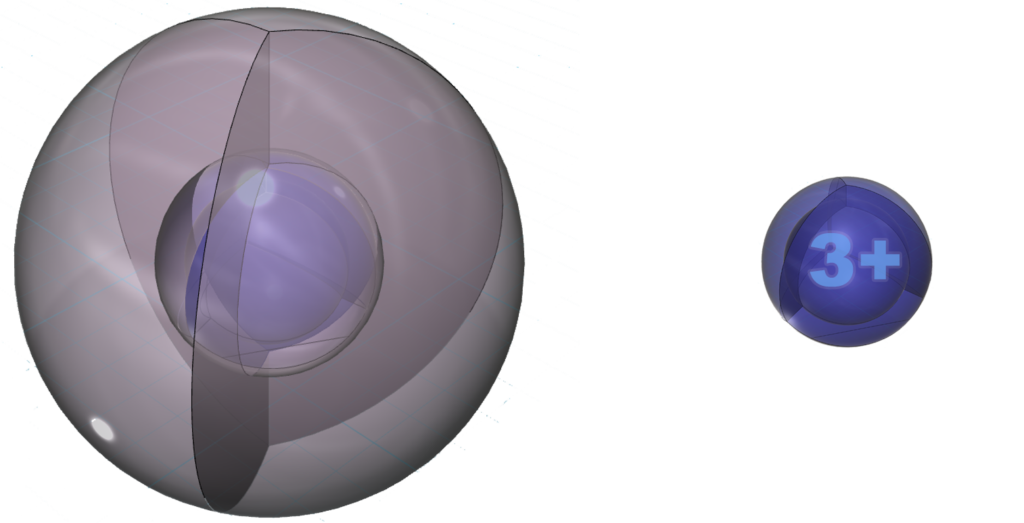

Aluminum will bond with other metal atoms via a metallic bond, and with non-metals via an ionic bond in which it loses its three valence electrons. It will lose all three at once in order to reach the stability of a full 2nd shell. This is the same electron configuration as the 2s22p6 noble gas configuration of neon — a multi-di-electron state with two concentric full shells. That is why aluminium forms a 3+ ionic state, as in aluminum oxide (Al2O3).

The positive ion is much smaller than the neutral atom because protons now outnumber electrons by three. This results in a much higher effective nuclear charge — a higher average attraction by the nucleus on each electron, which shrinks the size of the electron shell as it is attracted inward with more force.

Neutral aluminium (Al) atom (L) compared to the much smaller Al3+ ion (R)

Neutral aluminium (Al) atom (L) compared to the much smaller Al3+ ion (R)

Some uses & properties

Unlike most other small ions, aluminium ions do not play a biologically useful role. In fact, given their small size and high charge, Al3+ ions are toxic to most organisms.

Aluminium occurs in nature in a bonded, crystalline form. Reducing it to pure metal is done via electrolysis, and uses a large amount of electricity because it requires 3 electrons for every atom of aluminium to turn Al3+ ions into Al0 metal. One of the key uses of this light and strong metal is in the manufacture of aircraft. The first aircraft engine, built by the Wright brothers, was made out of aluminium specifically due to its low density, making for a lighter engine.

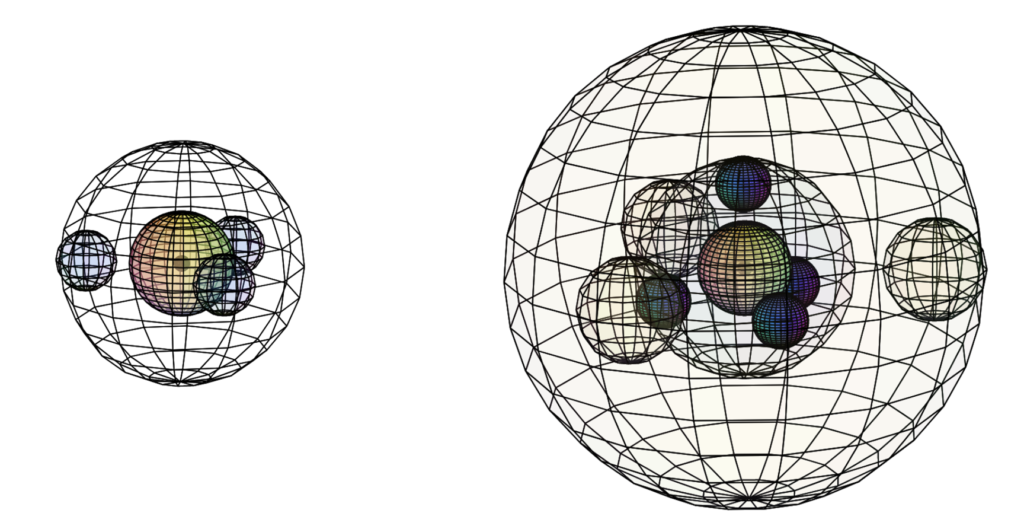

When we compare aluminium to boron (B), we see a significant size difference (see below). We also see a significant difference between the magnetic susceptibility of aluminium and the other Group III elements, since aluminium is paramagnetic (χm=+16.5) while the others are diamagnetic. Aluminium’s paramagnetic strength is also very similar to that of sodium (Na) (χm=+16).

Size comparison between boron (left) and aluminium (right)

Size comparison between boron (left) and aluminium (right)

This pattern might suggest that, in its crystalline metallic state, aluminium’s electronic structure and band-filling are somewhat unusual compared to a simple “three free electrons per atom” picture. In other words, while aluminium is conventionally treated as a trivalent metal in the band description, it may still be possible for certain bulk properties (especially transport and magnetic response) to be influenced disproportionately by one “more mobile” conduction channel, with the remaining valence character contributing differently through band structure, screening, and bonding. (This would not imply that two electrons remain literally localized on each atom, but rather that the metallic state can reorganize the valence character in ways that do not map one-to-one onto the isolated-atom picture. In compounds, by contrast, differences in electronegativity and bonding strongly favor aluminium’s familiar trivalent ionic behavior.)

If this speculation is even partially on the right track, it could help frame the following observations in a cautious way:

aluminium has a magnetic susceptibility value similar to sodium (Na).

aluminium has a 2nd ionization energy whose increase is notably larger than the elements on either side of it (Mg & Si). While ionization energies are atomic (gas-phase) quantities and do not directly determine metallic conduction, the size of this jump is at least consistent with the idea that removing additional valence electrons from aluminium after the first can be comparatively “costly” in the isolated-atom sense, even if the metallic state distributes these electrons into bands rather than keeping them as discrete atomic electrons.

aluminium is a soft metal. It seems reasonable that bond strength and hardness are shaped not only by electron count, but by how the bands fill, how effectively the electrons screen ion cores, and how easily the lattice accommodates dislocations. In that light, an “effective” carrier picture in which one portion of the valence response dominates conduction does not contradict aluminium’s softness, and may even be compatible with the idea that aluminium’s metallic bonding is comparatively less stiff than one might naively expect from a purely trivalent caricature.

If aluminium behaves, in some measurements, as though a smaller subset of carriers dominates electrical transport — somewhat reminiscent (in effect, not in literal electron count) of copper (Cu), silver (Ag), and gold (Au) — that could help motivate why aluminium is among the very best electrical conductors in practice, typically ranking just after silver, copper, and gold, despite being a much lighter and more reactive metal. (Here, the main point is not that aluminium truly has “only one delocalized electron per atom,” but that its conduction and magnetic signatures can be shaped by band structure in a way that sometimes makes it look more “one-carrier-like” than a naive valence tally would suggest.)

Boron’s diamagnetism (χm=–6.7), on the other hand, would appear to emerge from the fact that it usually makes covalent bonds, in which all of its electrons are paired

RETURN to the Periodic Table